Dear All,

I decided to move the blog directly on my website www.andreacaputo.org.

You can find all the old article there.

See you there ;)

Andrea

The Cap's Blog

Thoughts, ideas and considerations about the World

venerdì 14 settembre 2012

mercoledì 5 settembre 2012

[Last] Episode: What is changing in manufacturing

Usually when we refer to production,

factories and industries, we all think about the production function. As we now

an output is mainly made by Labor, Capital and Land. The way they combine

together is called technology. As I reported in my previous posts

technology is deeply changing. During the 20th century technology

had a lot of innovations. By thinking on processes we shifted from the mass production of the beginning of the

century to lean production in the

1990s. Yet we needed a huge amount of capital, land and labor. Thus, companies

moved from richer countries to poorer as the process of globalization gathered

pace. Poorer countries allowed the same production level for less capital, land

and labor costs. Costs not technology. Yes, the famous abroad outsourcing

process wasn't a technological breakthrough. It was simply a movement, allowed

by transport cost reduction and internet communication, from a high-cost place

to a low-cost place. The technology of production didn’t change at all or so. But

now something is changing. New production machines as 3D printing allows people

to produce some products (even iPhone or car parts) directly at home (at $

1,299 you can buy a 3D printer). Furthermore, people having ideas and no money

now can go online and see their ideas produced and sold, and they gain 30% of

the profit. I don’t know if this is a revolution but it seems to me. For sure

is big change. Let’s see what and how is changing in production.

The figure of the entrepreneur and the role of capital

in production could change. Henry Ford needed heaps of capital to build

his colossal River Rouge factory; his modern equivalent can start with little

besides a laptop and a hunger to invent.

The factory

will change. The factory of the past was based on cranking out zillions of

identical products: Ford famously said that car-buyers could have any colour

they liked, as long as it was black. But the cost of producing much smaller

batches of a wider variety, with each product tailored precisely to each

customer's whims, is falling. The factory of the future will focus on mass

customisation—and may look more like the 18th century weavers' cottages than

Ford's assembly line.

The geography

of supply chains will change. An engineer working in the middle of a desert

who finds he lacks a certain tool no longer has to have it delivered from the

nearest city. He can simply download the design and print it. The days when

projects ground to a halt for want of a piece of kit, or when customers

complained that they could no longer find spare parts for things they had

bought, will one day seem quaint.

The role of labor in production will change. Labour costs are growing less and

less important: a $499 first-generation iPad included only about $33 of

manufacturing labour, of which the final assembly in China accounted for just

$8. Offshore production is increasingly moving back to rich countries not

because Chinese wages are rising, but because companies now want to be closer

to their customers so that they can respond more quickly to changes in demand.

And some products are so sophisticated that it helps to have the people who

design them and the people who make them in the same place. The Boston

Consulting Group reckons that in areas such as transport, computers, fabricated

metals and machinery, 10-30% of the goods that America now imports from China

could be made at home by 2020, boosting American output by $20 billion-55

billion a year.

Source: The Economist, Special Report on Manufacturing and Innovation,

A third industrial revolution, April 21st 2012.

lunedì 3 settembre 2012

Third Episode: Collaborative production, from outsourcing to crowdsourcing

In 1950, in the era of mass production, New

York City was the capital of manufacturing in America, with 1 million of people

working in the sector. Today only 80,000 people are employed in the sector, largely

by specialist producers. Yet nourished by the city’s entrepreneurial spirit, a

new industry is emerging. It might be called social manufacturing.

Quirky, for example, is a design studio

with a small factory complete with a couple of 3D printers, a laser cutter,

milling machines, a spray-painting booth and other bits of equipment. This

prototyping shop is central to their business of turning other people’s ideas

into products.

Yes, have you ever had an idea about a

product with no knowledge on how to build it? Now you know Quirky exists. The

process works like this: a user submits an idea and if enough people like it,

Quirky0s product-development team makes a prototype. Users review this online

and can contribute towards its final design, packaging and marketing, and help

set a price for it. Quirky then looks for suitable manufacturers. The product

is sold on the Quirky website and, if demand grows, by retail chains. Quirky

also handles patents and standards approvals and gives a 30% share of the

revenue from direct sales to the inventors and others who have helped. In this

way, Quirky can quickly establish if there is a market for a product and set

the right price before committing itself to making it.

Shapeways is an another online

manufacturing community, it specializes in 3D printing services. It shipped

750,000 products last year. Users upload their designs to get instant automated

quotes for printing with industrial 3D printing machines in a variety of

different materials. Users can also sell their goods online, setting their own

prices. Some designs can be also customized by buyers.

Easy online access to 3D printing has three

big implications for manufacturing:

1.

Speed to market is increased

2.

Market risk almost inexistent:

entrepreneurs can test ideas before scaling up and tweak the designers in response

to feedback from buyers

3.

It becomes possible to produce

things that cannot be made in other ways, usually because they are too

intricate to be machined.

Once in digital form, things become easy to

copy. This means protecting intellectual property will be just as hard as it is

in other industries that have gone digital.

MFG.com, another online production service,

provides a lot of services with more than 200,000 members in 50 countries.

Firms use it ot connect and collaborate, uploading digital designs, getting

quotes and rating the services provided. This could tunr into the virtual

equivalent of an industrial cluster.

Dassault Systemes, a French software firm,

has created an online virtual environment in which employees, suppliers, and

consumers can work together to turn nee ideas into reality. It provides

lifelike manikins on which to try out new products. They call such services

“product life-cycle management” because they extend computer modeling from the

conception of a product to its demise, which nowadays means recycling.

As digitization has freed some people from

working in an office, the same could happen in manufacturing. Product design

and simulation can now be done on a personal computer and accessed on the

cloud. It means people involved in can work from anywhere and share ideas. This

could means the factory of the future could be anyone sitting in his own

office.

Source: The Economist, Special Report on Manufacturing and Innovation,

A third industrial revolution, April 21st 2012.

mercoledì 29 agosto 2012

Second Episode: From mass production to smart production.

Additive manufacturing is not yet good

enough to make a car or an iPhone, but it is already being used to make

specialist parts for cars and customized covers for iPhones. Additive

manufacturing is only one of a number of innovative production equipment

leading to the factory of the future. Conventional production equipment is

becoming smarter and more flexible too.

For example, Volkswagen is implementing a

new production strategy called MBQ. By standardizing the parameters of certain

components they hope to be able to produce all its models on the same

production line (Again economies of scale).

Factories are becoming vastly more

efficient. Nissan’s British factory in Sunderland, opened in 1986 is now one of

the most productive in Europe. In 1999 it built 271,157 cars with 4,594 people

(59 cars per capita). Last year it made 480,485 cars with just 5,462 people (88

cars per capita).

As the number of people directly employed

in making things declines, the cost of labor as a proportion of the total cost

of production will diminish too. This will encourage makers to move some of the

work back to rich countries, not

least because new manufacturing techniques make it cheaper and faster to

respond to changing local tastes.

The materials are changing as well.

Carbon-fibre composites, for instance, are replacing steel and aluminum.

Sometimes it will not be machines doing the making, but micro-organisms that

have been genetically engineered for the task. Software are going smarter. And

the effects will not be confined to large manufacturers, much of what is coming

will empower small and medium-sized firms and individual entrepreneurs.

Launching novel products will become easier and cheaper. Communities offering

3D printing and other shared production services are already forming online.

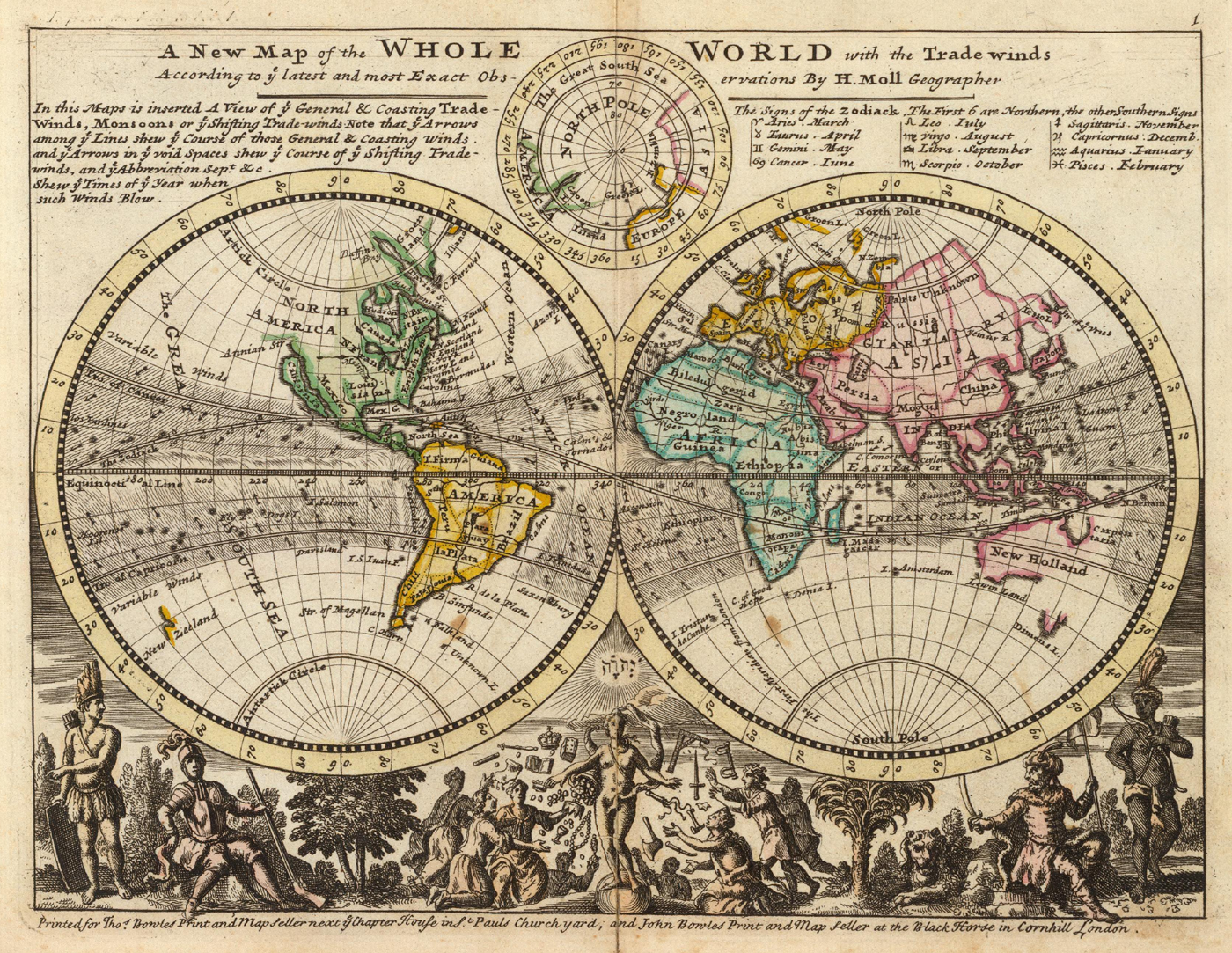

The consequences of all these changes

amount to a third industrial revolution,

as The Economist wrote in April 2012. The first began in Britain in the late 18th

century with mechanization of textile productions. The second began in America in the early 20th

century with the assembly line and the era of mass production.

As manufacturing goes digital, a third

great change is now gathering pace. It will allow things to be made

economically in much smaller numbers, more flexibly and with a much lower input

of labor. The first two industrial revolutions made people richer and more

urban. The third?

Source: The Economist, Special Report on Manufacturing and Innovation,

A third industrial revolution, April 21st 2012.

domenica 26 agosto 2012

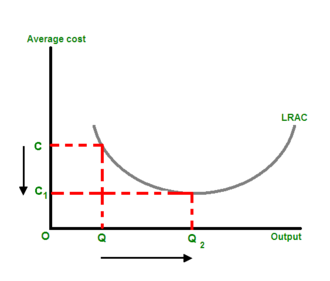

Pilot: Additive Manufacturing & economies of scale

Today I was going through The Economist's special report on manufacturing and innovation (published in April 21st 2012) and I decided to start a set of posts to explore some interesting insights about what The Economist called a third industrial revolution. (Please note the "a" instead of "the", we will see if there will be a change about it in the next few years)

Additive

Manufacturing is the process of producing parts by

successive melting of layers of material rather than removing material, as is

the case with conventional machining. Hence, choosing an AM technology for

production provides great benefits for the entire production value chain. The

geometrical freedom allows you to engineer/design your part as you envision it,

without manufacturing constraints. This can be translated to extreme

light-weight designs, reduced part counts or improved bone ingrowth for a

medical implant. It is also a fast production route from CAD to physical part

with a very high material utilization and without the need to keep expensive

castings or forgings on stock.

What could it mean?

Try today to go to a factory and ask to

make you a single hammer to your own design. The producer would have to design

and produce a mould, cast the head, machine it to a suitable finish, turn a

wooden handle and then assemble the parts. You will be presented with a bill

for thousands of dollars!

Thus, it would be efficient only if you produce

a certain amount of items, as the well-known concept of economy of scale says.

What is a technology breakthrough? It is

any significant or sudden advance, development, achievement, or increase, as in

scientific knowledge or diplomacy, that removes a barrier to progress (i.e. the

jet engine was a major breakthrough in air transport or internet was a major

breakthrough for communication). When this happens usually a market structure changes

as production changes.

Thanks to 3D printers and other additive

manufacturing tools, economies of scale

matter much less. In fact, its software can be endlessly tweaked and it can

make just about anything. The cost of setting up the machine is the same

whether it makes one think or as many things as can fit inside the machine. As

a normal printer, it will keep going at about the same cost for each item

(Obviously you would take into account the fixed cost and amortization of the

machinery – so economies of scale still matters but much less).

giovedì 23 agosto 2012

From HBR: See the Big Picture Before Making a Decision

Here is a good decision-making advice from today HBR's Management Tip.

Successful strategic thinkers always have perspective. They consider the potential impact of their actions on those beyond their team or unit. Next time you need to make a big decision, here are three ways to make sure your thinking isn't too narrow:

- Explore the outcomes. With every idea, ask yourself, "If we implement this idea, how will other units and stakeholders be affected? What might be the long-term ramifications?"

- Expand your range of alternatives. Gather ideas and concerns from everyone who has an interest in the decision or who will be affected by the outcome.

- Consider the customer. Look at the decision through your customers' eyes. What will they think and which alternative will they prefer? If you're not sure, think about asking them.

venerdì 10 agosto 2012

Are Italians knowing Car Sharing? (finally after almost 10 years of activity)

A recent TV report from the Italian television (SuperQuark of July 26th 2012 - Rai1) showed me that finally Italy is knowing what car sharing is.

I have known Car Sharing since 2007, when I wrote my bachelor thesis on it. Since that time Car Sharing has been always in my research interest, and I am now writing a paper about it.

Here is the abstract!

Car

sharing, an innovative mobility service complementary to the local public

transport, helps, through the sharing of a fleet of cars among users, to reduce

individual and social costs of private transport, at the same time avoiding the

rigidity of traditional public transport as well.

My paper on car sharing intends to explain the nature and development of car sharing through

three key directions: i) the critical analysis of literature, through which it

was possible to identify how car sharing is still not very extensive; ii) the overview

of the Italian context; and iii) the analysis of car sharing service in detail,

through a case study of the experience in the city of Genoa.

The

purpose of this paper is to contribute to the few existing studies on car

sharing in an effort to increase academic and managerial attention on this

sustainable mobility service.

Iscriviti a:

Post (Atom)